Analyse October 2016

The whys and wherefores of negative interest rates – and the prospects for change

They strike fear into the hearts of the general public and investors alike. They are upending the usual way in which banks do business and make money. Negative interest rates – a singular occurrence in the history of finance – are bad news for both the economy and financial markets. But we are getting used to them. After all, some parts of the economy have no choice other than to play along. Still, the days of negative rates are probably numbered.

Negative interest rates have brought about a strange, perhaps absurd, state of affairs that was previously unknown to the purveyors of economic and financial theories. As homo economicus , we think and act rationally. When we invest, we expect to earn a return on that money. In 5,000 years of documented history on the activity of lending and borrowing, there is not a single trace of a ‘negative’ interest rate. The once-safe concept that money ‘works for us’ when we invest it has broken down.

Central banks are keeping monetary conditions extremely loose, which is adversely affecting deposits but at the same time lowers the cost of borrowing. The Bank of Japan and the ECB are both applying negative rates (e.g. -0.4% for the ECB’s marginal rate) to coax expenditure in the real economy, stimulate inflation and pin down the exchange rate. A lower exchange rate in turn makes a country’s or bloc’s exports more competitive. Another effect of negative interest rates is that they redistribute wealth between lenders and borrowers.

Negative yields are furthermore a sign of economic stagnation. Shifts in the population make-up and in the fabric of societies are eroding productivity gains and resulting in a low marginal return on capital. There is only so much monetary policy can do to solve such problems.

Long list of drawbacks

As uncharted territory, negative rates are seen by many as controversial. Established economists, researchers and bankers are increasingly warning of the dangers of negative rates while questioning how effective they have really been. We could be forgiven for thinking that central banks have messed up, given the long list of unattended consequences to date. Though still too early to draw conclusions, the benefits to the global economy have so far been minimal. Corporate capital spending is still flat-lining. At the same time, the financial climate has become more unstable because of the damage being wrought on banks. In Euroland, there has been no surge in retail lending for the simple reason that there was already an amply supply of credit.

Meanwhile, savers – who are earning almost nothing on conventional products – have become disgruntled. At the same time, the business models of banks, insurers and pension funds are falling apart at the seams. Interest margin, the cornerstone of retail-banking income, has been cut to the bone. And as if that was not enough, negative interest rates are fostering a mood of anxiety among consumers and investors. The latter are scared of losing money if they venture into other types of asset, so they are stomaching minor losses on their cash holdings.

Disruptive influence of negative rates

Notwithstanding, negative rates are becoming more prevalent in the world. Institutions such as pension funds and insurers are having to acclimatise to the new paradigm. Given their duty to protect the money which they invest, there is no alternative. Some private-sector investors are also playing along, anticipating even lower rates that will usher in an era of deflation.

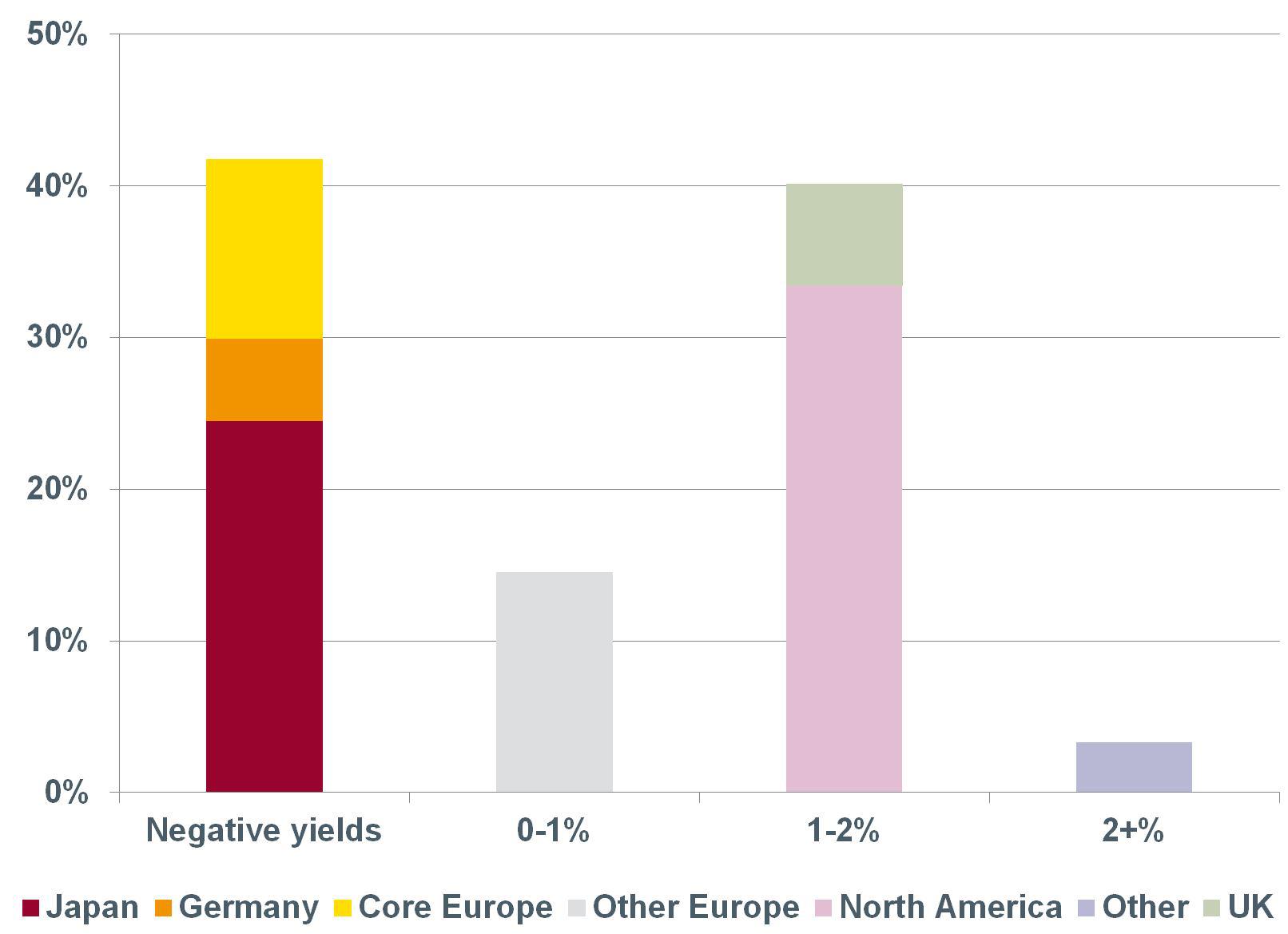

The outstanding amount of negatively priced government bonds has swelled to USD 13 trillion, including over 8 trillion of Japanese government bonds (see Chart 1).

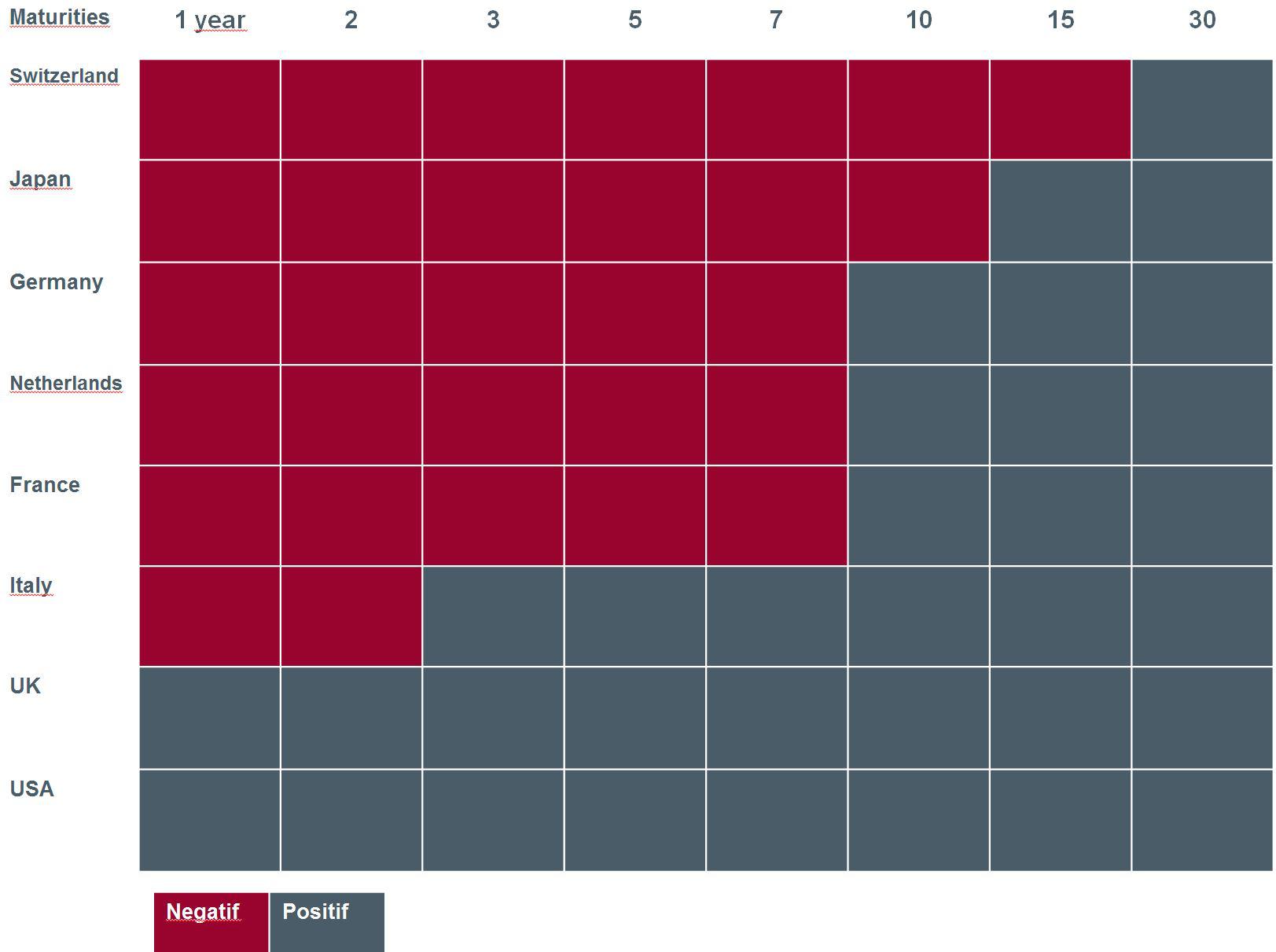

Top of the class is Switzerland, whose yield curve is in the red at every maturity (Chart 2) – a sign that investors expect negative rates to remain entrenched there.

On whether negative yields could take hold over the long term, or whether this is a transitory episode, we would lean towards the latter idea. With little to show for the austerity policies that they have been enacting, national governments – most notably in Europe and Japan — will sooner or later revert to expansionary policies. The resulting increase in the supply of sovereign bonds, issued to fund higher public expenditure, would probably push bond yields upwards.

Pragmatically, then, each and every investor is wondering how to generate a modicum of yield without taking on an enormous degree of risk. In this setting, the shares of companies paying a steady dividend (think consumer goods and pharma) are worth a punt, especially since such firms may feel compelled to repurchase shares to reduce losses on their cash holdings.

Fig. 1 Government bond yields – developed countries

Fig. 2 Bond yields by maturity

Analyse

Analyse